After Solstice

And a July excerpt from Uprooting

The ash tree at the top of the garden is dying. The father of the garden, my daughter calls it, it feels more like a grandfather in its stature and age. Soon it will fall. We do not yet know how the new light will dance across the garden in the shadow of its passing.

Shrubs die in the harsh winter. Shrubby germander, hebe, phormium. We dig them out. The box blight is worse than ever, so we remove all that is sickly constrained. Two conifers that must have been bought by a past inhabitant of the garden as tiny domes in nursery pots tower over the space, hoard the light. My husband digs their thick trunks out; afterwards he sits muddy, red-faced and gasping in the kitchen at the effort.

I take pictures of the garden. I take pictures of myself; I’m not sure why. To document the change, like I documented my changing body – as if that could capture my changing self – in the months of pregnancy, the time after giving birth. I look hollow-eyed and exhausted, or smiling and glowing, depending on the light.

A season of change is upon us. Swept along in the momentum we take out other things too, plants whose presence we have wrinkled our noses at, but not removed because why would you remove a perfectly good plant? They go. Not everything rooted in place belongs here. We take away the rotting old veg beds, scaffolding boards finally collapsed upon themselves too dangerous to plant, to climb. We drag all the old wood too rotten or diseased to use for firewood into a huge pile of brush in the middle of the meadow. On Beltane we light the fire. It crackles and leaps so far and high that uppermost branches of the quince are scorched. The cool, drying northeast wind blows the smoke of the fire over the garden. A cleansing.

A story I have told before, the same but different in its retelling. What grows into the vacuum?

A pair of new walls are built to hold up the garden. A site for offerings from an old temple sits within them, where a candle burns for solstice. Gloworms burn a green counterpoint, their number many more than previous summers. Beetles cover everything, moths softly flutter around bulbs at bedtime, a tiny invertebrate crawls across the glowing screen between these letters as I type them. The walnut tree that was suffering in the conifers’ shadow puts on a foot of new growth. I plant a philadelphus I have been dreaming of in the germander’s wake and its scent drifts through the garden for weeks. The phlomis flowers and for the first time we really see it. The ornamental raspberries expand to swallow the gaps, leaving no trace of what was there before.

The ash tree comes into fuller, healthier leaf than we have seen. A friend sends a link to a talk online, saying how up to a third of mature ash trees are proving resilient to dieback, how the stream at this one’s roots may be protective. We squint at the crown, no longer bald. In the heatwave we stand in its shadow, grateful for its cool shade in the harsh light of this climate crisis.

So much can happen in a growing season.

It is the full moon but I cannot see it for cloud. The full belly of the moon represents release. It is a death. It is a birthing. I remember the full moon of my pregnancies, the round dome of a baby crowning. My old self dying in the shimmering light of the euphoric agony of birthing new life. How long does a story gestate? On tonight’s full moon something calls me to light a votive in the garden’s niche – or is it a new altar? I sit in the shadow of the flickering light and listen to the noisy quiet for a while. Soft rain comes. My soul bleeds into the soil.

In four weeks’ time it will be the full moon of Lughnasadh, the beginning of the year’s harvest. In four weeks’ time I will reap what I have sown as Uprooting is birthed into the world.

An excerpt from Uprooting

The crocosmia are in their fullest glory for weeks, flying above the garden in their unmissable bright red. They look so tropical, and therefore wildly out of place in my imagined vision of an English country garden. But my ideas of what is tropical and what belongs in an English garden have been profoundly upended. I read that crocosmia are fully hardy here, even escaping from gardens to make themselves at home in the landscapes of the Hebridean islands. I take photos of them in the garden from every angle, tilting my phone camera this way and that, contorting myself into odd shapes around them, trying to capture this sense of them suspended in flight. I post the photos online and look at them on my screens later. Rubies sewn into the garden’s green cloth. Blood Pollock-spattered across the landscape.

I am able to spend more and more time outside again, and find myself there frequently, unthinkingly taking my grief into the garden. The busyness of spring tasks seems to have slowed. There is watering to be done, of the houseplants which I place out on the patio for a summer vacation, and the annual veg. For the garden, I take advice that I see online to water the plantings in the veg beds thoroughly but relatively infrequently to encourage the growth of deep roots. Ornamental perennials I have watered-in on planting, dipping the watering cans into the pools formed along the stream’s course, and then left them largely to their own devices. The rains have returned, and there seems to be plenty of water held in the clay, and I am hopeful that the mulch, and all the creatures and worms that have followed it, will help make the nutrients trapped in the soil available to the growing plants that need it. I am doing my best to help the earth of this garden become as healthy a soil as possible. In doing so I am trusting that the plants will be given the resilience they need to thrive.

The biggest call I feel from the garden now is to move languorously along the paths and enjoy it. I step outside and wander around the beds, listening for the call to do, to tend, but there is little. The midsummer stillness feels oddly like midwinter, a pause, this time at the top of the expansive inhalation of the year before the swooping exhale into eventual darkness. We are near the peak of growth. The garden is tumbling well out of my control, its lush growth reaching up, out and over, beyond any limits I could have imagined. In places I tie things in to makeshift supports, where they begin to encroach on the path so much that we cannot pass, or collapse onto and inhibit their neighbours. I add ‘supports – rusty metal?’ to my list of garden desires, although this feels more like a need. The sheer abundance of it overwhelms me. I have never received such a generous gift.

There are so many flowers, but I read that to have even more I must cut them, and delay the plants’ going to seed. Something about that line of thinking feels cruel, but I spend an evening with a glass of wine, after the children have gone to bed, deadheading the spent flowers of the purple daisy, whose shining bank of blossom lights up the conservatory. The repeated cuts are cathartic, and I am rewarded later with a fresh flush of bloom. It feels less callous to think of sharing the prolific blossom so generously offered. I pick posy after posy, and while they are beautiful in the house, I especially enjoy leaving them on the doorsteps of others to return their kindnesses. Generosity multiplying many times over.

As I feel the garden grow well beyond anything of my doing, it is disturbing to realise that I have no true control over this space. I might cut it and trim it and prune it to create that illusion, but I begin to feel the deep reality that these plants are beings with a life and a will entirely their own. In the bare earth of spring, I planted two Thalictrum delavayi side by side. One of them is towering upwards, covered in buds and soon to flower. The other has disappeared, seemingly dead. I am coming to realise that while I may think of it now as my garden, I am at best a co-creator in this space. My planting is mere suggestion; the plants interact with each other and this unique place to grow new possibilities beyond my limited human imagining. I am just one more creature who might grow, maybe even bloom, in this fertile space.

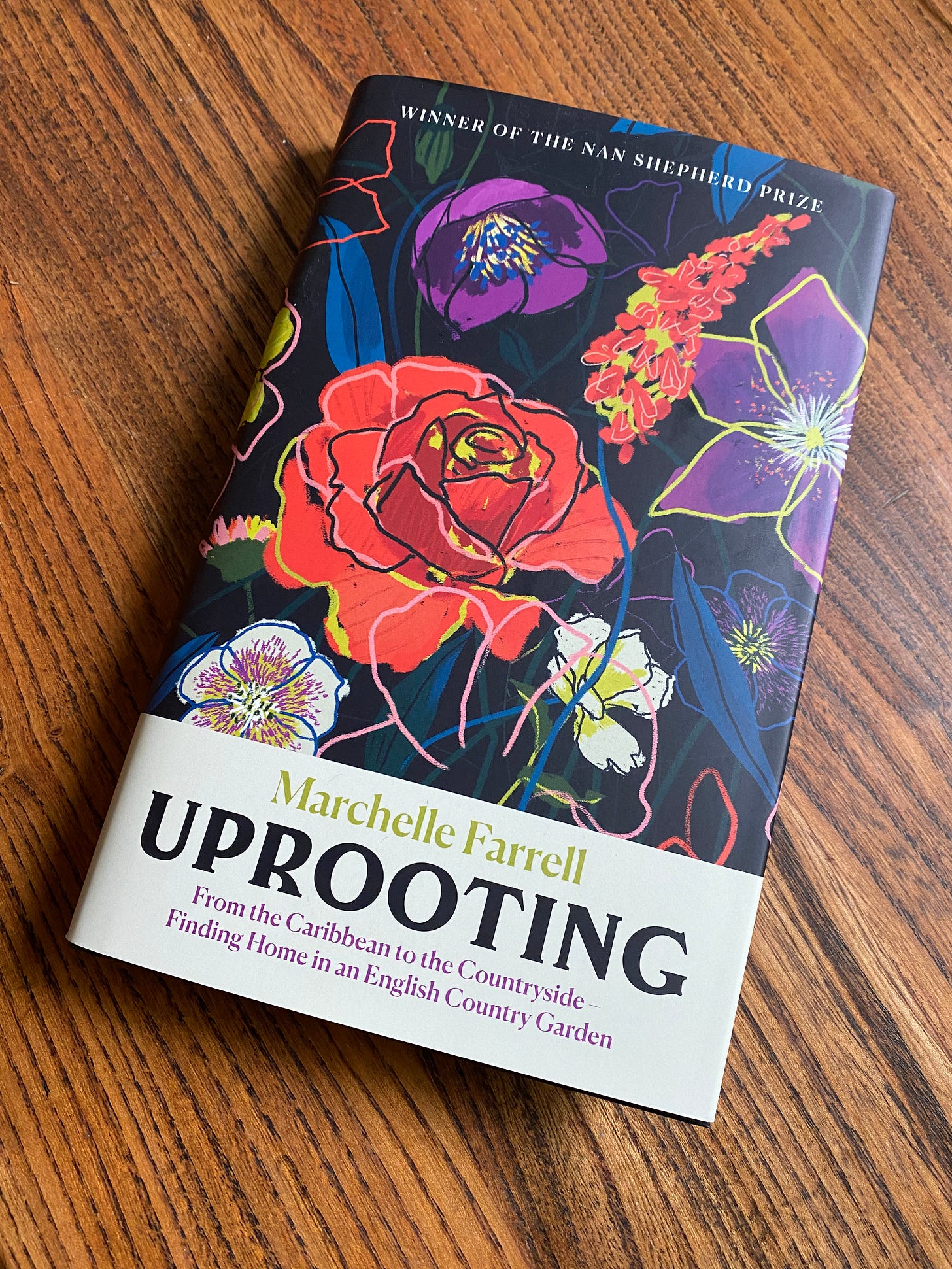

I am so looking forward to the fertile space of meeting and speaking with you about Uprooting once it is out in the world, and it is so very nearly out in the world. I recorded the audiobook, which was exhausting and emotional, and then my first print copies arrived unexpectedly this week. I had to go and sit with my overwhelm awhile in the garden. I cannot wait for you to read it.

The first couple of events that I’ve done with the book as a complete being, at the Tate and Brighton Book Festival were such joyous occasions. It is a delight to be shown the fires lit by the sparks of my words, and wonder what next they might go on to set ablaze. There will be many more events in the months to come. I hope to meet many of you! I will try to keep the list of places where the book and I will be updated here as they are confirmed, as well as posting about them on social media, and hopefully I will be at an event, or an independent bookstore near you soon.

Uprooting will come at Lughnasadh, at harvest time. Until then, it’s still the season of growth. Of blossoming, of fecundity, of pollination, of ovaries slowly ripening into fruit. May your summer be a lush and beautiful one.

Some of you have kindly asked how you might support my writing. Your time and attention on my words is a priceless gift in itself. But if you would like to encourage my writing in material ways, please consider pre-ordering my book, Uprooting, for yourself or a friend. Which feels a strange thing to ask in this economy. Perhaps you could let others know about it, or ask your local library to get a copy. It will be out in the world on August 3rd, to lead a new life of its own. I hope you will love it.

Your writing is beautiful. Congratulations on the book, and every success with it! 💕