Ēostre

I woke up thinking of the garden, which is as it should be. Of putting my hands to the crumbly dark earth and meeting its creatures living there. Of plants: the cutting back of old growth, the tender green shoots emerging, made suddenly more visible, more hopeful.

Every spring the garden is born again and it shows me how. How to die. How to leave the past standing, where I may know and contemplate it, protecting new growth as it stirs within from cold burns that would ravage it while still tender and young. How to let things rot when no longer needed, so that in their composting they fuel the regeneration of the world to come. I woke up thinking of the garden and it taught me how to live.

Yesterday I did the kind of transformative gardening that changes something in me. Slow, immersive work, repetition of my body that stills my mind. That requires focus but not too much concentration, so that my mind can soar, and dance, and play while my hands are tethered to the soil. The kind of task that you stand up from after a while, back and knees stiff, and the space looks different and you can see the changes you have made in just a few dedicated hours.

So much can happen in a growing season.

There is a pigeon on the deck watching me. It sang happily on the balustrade until we made eye contact, and now it is silent, on high alert, checking me out. I wonder how their brain makes sense of two images from opposite sides of their head at the same time. And we consider ourselves the more sophisticated minds. Eventually, it seems to accept me. It begins cooing again, a whole body song. I have never noticed before that a pigeon sings with its whole being. And then some early morning cyclists swoosh down the quiet hill and away it flies to the woods.

Eyes drawn to follow its flight, I notice the first wash of green on the trees opposite. It surprises me. I sat here yesterday and swear that vivid flush wasn’t there. Or I didn’t notice it. The woods looked ugly to me yesterday. Today my nose streams with allergies to the birch flowering potently across the road but still everything looks more beautiful. I love it more.

I love it because I have tended it, spent hours with my hands in contact with the soil, preparing the veg beds – no longer barren spaces, rich with weeds and other life – to receive my spring plantings. And in that care, it has tended me. Grown inside me and changed something profound in how I look at the world, the ugly made beautiful.

I don’t know about hope but I know about love. This act of reaching towards the other. This tender, open vulnerability that lets the other reach you. This fertile coupling that lets new life in.

An Easter preview of Uprooting

The magic of Easter has always been my favourite – extremes of death and rebirth, all in one chocolate-coated holiday weekend. I was raised in a deeply Catholic setting. My father, born a Seventh Day Adventist but who gave up that church on leaving home, still retains a profound knowledge of Bible verse. My mother, immersed in Catholicism, her father a lay minister in the church, her mother in the choir. The scandal of my mother’s belly swelling while my parents were unmarried students, and their Adventist wedding shortly before my arrival, perhaps forgiven, never forgotten. In true Catholic fashion, I still carry the guilt.

I spent twelve years at a Catholic school, the secondary years girls-only, and was taught by Dominican sisters, one of a few local chapters of nuns. It was a nurturing school where I felt known and loved, but the devotion to the higher spirit that it demanded, with a repression of earthly desires, was not without sacrifice. We were taught to despise the precious homes that were our earthly bodies, to be ashamed of the dirt of our flesh. We crowned Mother Mary with flowers, but were always aware that we were Eve after the Fall, debased, our highest aspiration to cut ourselves loose from this sinful, dirty place we temporarily inhabit. The ultimate conquest of our colonial invaders being the severing of our souls from the daily miracle that is life on this earth.

Christianity was closely linked to slavery. In the early days of the development of the plantations, European indentured labourers worked alongside African slaves, both receiving horrific treatment, but with a much more fluid social position that was not yet set in an ideology of racial inferiority. But to prevent the groups banding together in successful uprisings against their masters, a system of preferring the Europeans over the Africans was instituted by the plantation owners. This was initially based on faith, with Christian lives considered more worthy than non-Christians, who were seen as subhuman. Over time, and influenced by ideas such as the writing of Edward Long, a slaver who published the History of Jamaica, the classic text of pseudo-scientific racism, this faith-based hierarchy became a race-based one, with a shift in the privileged class from being called Christians to Whites.

In my childhood I was a profound believer, thumbing the rosary in my pocket, Hail Marys never far from my tongue. I feared God and liked Jesus, who seemed a kind man with sensible teachings, but Mary was the one I truly worshipped, a slightly blasphemous bent to the primacy of her place in my affections. It was Mother Mary that I turned to in my childish distress. It was she that I chastised when I turned sixteen and learned the church’s views on contraception and abortion and the strict policing of sexuality. She that I berated when I lost faith in the institution run by these holy men that seemed hell bent on suppressing my womanhood. But it was too late for my early childhood ease with prostrating myself in the dirt. I had repressed those urges. I had risen above such things.

For years I floundered in what I called atheism, but was really scientism, the redirection of my devotion towards those White men in white coats who would teach me the truth of the world. I believed in my studies fanatically, until I was working as a doctor with real patients and realised that, no matter how much I applied the Word of Medicine, there was still so much I did not know, that we could not know. So many mysteries of suffering of body and mind that seemed unanswerable when studied under the limited light of these truths. And the default professional response to the discomfort roused by inevitable uncertainty seemed to be a disdainful dismissal of any concern that could not be contained within a neat diagnostic box, cured with the clean cut of a knife or a pristine pill.

My own prostration as a patient was my biggest test of scientific faith. No investigations or examinations could answer the mystery of why my husband and my seemingly healthy young bodies were infertile. My acupuncturist, practising the techniques of a different faith, offered a clue, and deep within my body told me the answer, but I was afraid to hear it. Unwilling to make the sacrifices at the altar of my career that were called for.

One Easter I stood in the church in my in-laws’ village, attending the service we had been invited to as part of the family’s weekend celebrations. We had been trying for a baby for five years with no success. It had been many years since I had even had a miscarriage; my body now gave no sign that it might be capable of carrying a baby. When called in the service to a time of prayer, I bowed my head and thought of the goddess Ēostre.

I had begun to be curious about the Indigenous religious festivals of this island, of the ways of worship that pre-dated Christianity. I knew very little about what rituals and ceremonies there might have been on the islands of my childhood, but imagined that they would have been rooted in that very different landscape from which I was now cut off. So I turned to the old rituals of this island on which I was trying to build my home.

I was intrigued by the Celtic wheel of the year, and the way it seemed to punctuate even the darkest times with regular points of light. It was an ancient calendar that marked eight annual points with seasonal celebrations. I had a growing sense that leaning into the seasons, embracing even the cold and dark ones that I dreaded, might help my sense of belonging and connection to this place. I started venturing out into the landscape every six weeks with Oli and the children, seeking in some informal way to mark that point in the year. We took small picnics, gathered flowers or leaves, fruit or twigs, and used them to make something beautiful. I was taken by the stories of the goddesses, intimately intertwined with the elements and the plants, powerful mythical figures deserving of worship in their own right, unlike the subservient image of Mother Mary.

Ēostre, spring goddess of the festival Ostara, held at the vernal equinox. A time of the renewal and re-emergence of life after the death of winter, a celebration of fertility. I held a wordless plea in the silence of my mind, standing in a Christian church but directing my unformed thought, my bodily desire, to much more ancient forces. A prayer that my womb might hold the baby to come from the IVF cycle we were due to start at my next period. A hope for my fecundity.

There is debate as to whether Ēostre was a truly ancient pagan deity or simply invented in the ninth century by Bede. But the two lines on the strip of plastic that lay before my disbelieving eyes a couple of weeks later restored my bodily faith. My womb was a home to that baby; the magic of Easter gave birth to my son.

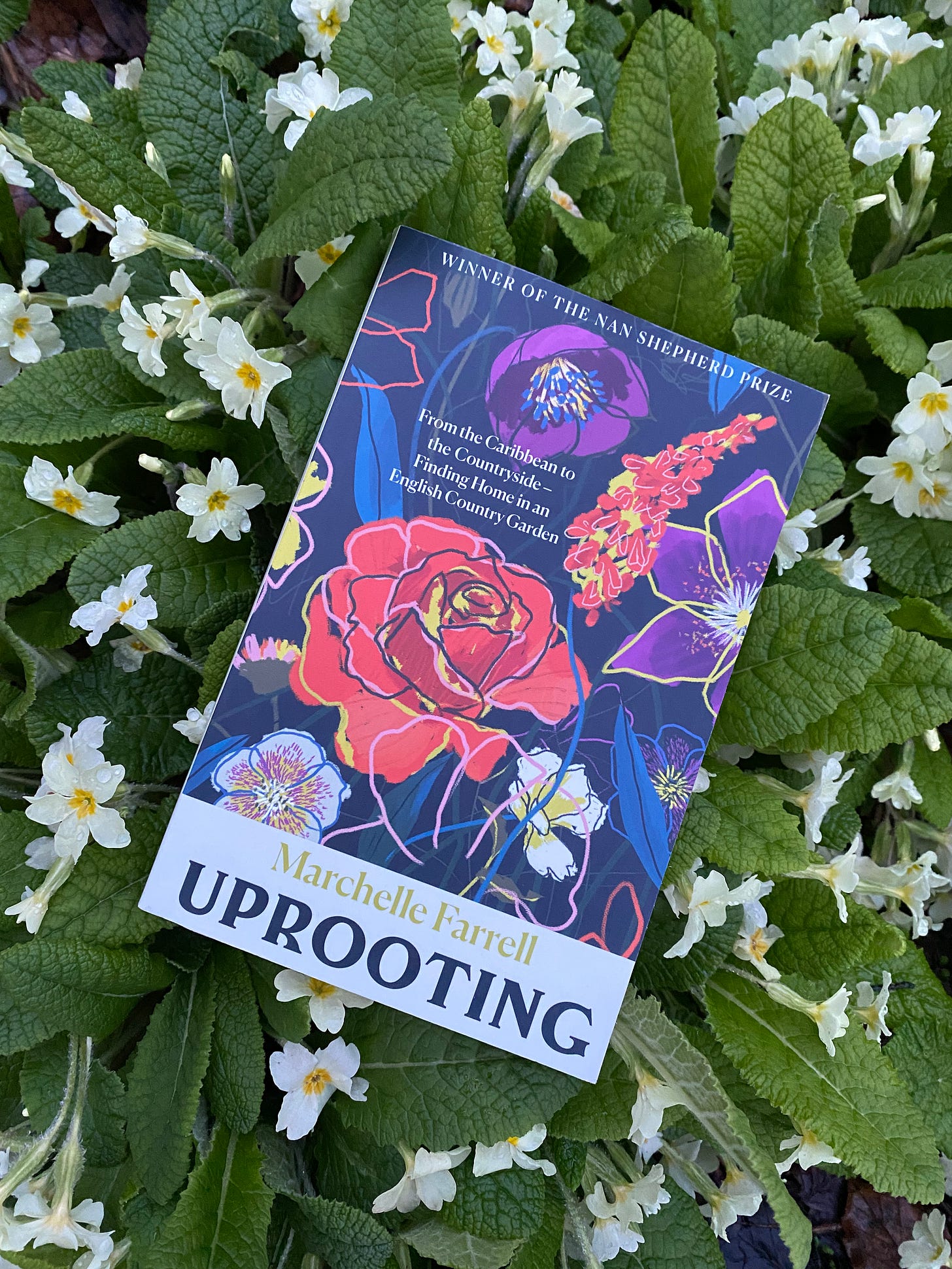

Some of you have kindly asked how you might support my writing. Your time and attention on my words is a priceless gift in itself. But if you would like to encourage my writing in other ways, please consider pre-ordering my book, Uprooting, for yourself or a friend. Which feels a strange thing to ask in this economy. Perhaps you could let others know about it, or ask your local library to get a copy. It will be out in the world on August 3rd, to lead a new life of its own. I hope you will love it.

What a benediction to read this on Easter morning. Your writing touches me, as a woman, a writer, a raised Catholic atheist who finds religion in the sun and soil, in the coaxing of life out of seeds. Thank you. I can not wait to savor your words in a book.

🧡✨✨ what a gift to read this this morning